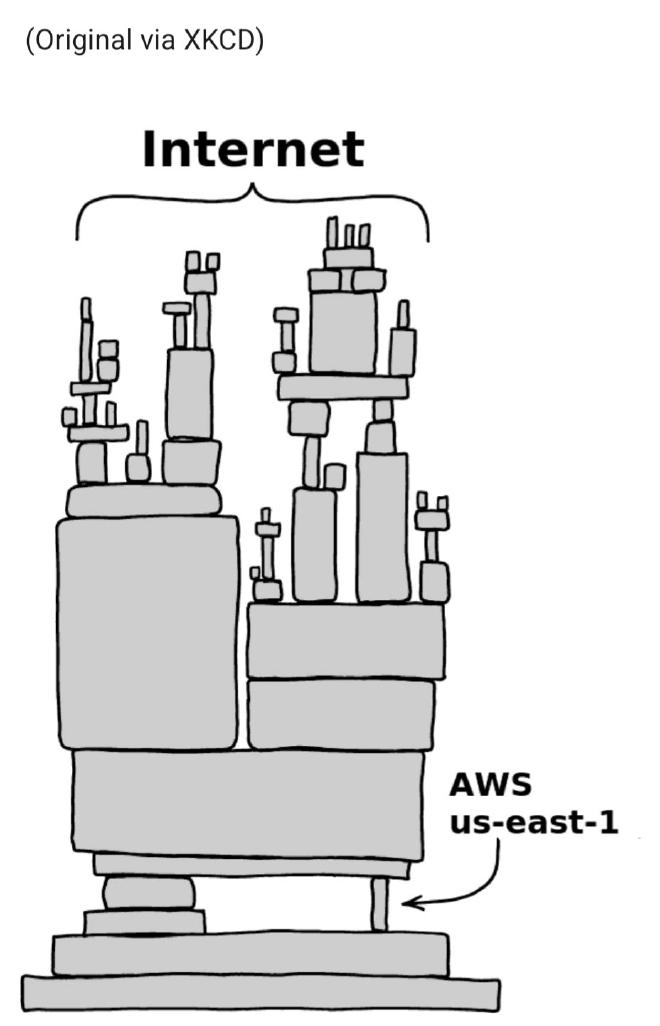

Thoughts about the us-east-1 incident

I didn’t see anyone complaining about Netflix being unavailable. Why?

Last month, I heard people complaining that their production website, which is used by their customers, wasn’t online and had availability issues. The fun (and irritating fact) is that the world’s most important website (by their saying) was hosted in a server room behind a parking lot, with no UPS, no redundancy, and a single consumer-grade internet connection. Needless to say, there was no DR site, and the server room’s only purpose was to help small offices host local NAS and small internal services.

I found the rage about us-east-1 issues similar to the example above.

What I am seeing is that humans prefer simple solutions, so blame AWS! Blame the region where everyone deploys their applications without knowing that things can fail, instead of analyzing why most of the companies deploy heavily used services in a single region.

Alessandro, in his post, gives a clear view of the issue.

If you host all your applications in a single data center and, for example, a blackout occurs, you’d better have a strategy for dealing with the issue. The strategy could be to make your infrastructure available in another data center, declare a disaster, initiate disaster recovery in another location (with different approaches), or blame the provider.

The truth is that the companies that knew that downtime could negatively impact their business had already set up countermeasures to survive: Netflix wasn’t down, Slack had minor glitches, and many other services weren’t hosted on us-east-1.

Some companies, maybe, had a Disaster and Recovery plan, but their Recovery Time Objective (RTO) was higher than what their users expected because the economic impact of downtime is higher than maintaining an active-active multiregion deployment (this could open an entire new thread about bad technical choices that impact the ability to deploy in a multi-region environment, but let’s stay on the topic).

Others could have decided that a regional failover wasn’t worth the effort of failing back, so they sat and waited, hoping that everything could be working again in a matter of hours.

Some companies could have everything in place, but they didn’t consider the technical bits: if the Route53 management APIs are down, and you cannot switch to a failover region. This could be resolved using Route53 Application Recovery Controller or Route53 healtchecks. When I conduct Well-Architected Reviews, I spend at least 5 minutes explaining the “Rely on the Data Plane and not the Control Plane during recovery” check, because in these situations, it makes the difference between surviving a failure and failing miserably to apply a previously good DR plan that didn’t take this aspect into account.

As a service user, you can demand better SLAs, but expect charges to increase because decreasing RTO to zero means increasing billing, development, and project complexity costs. It is also true that a lower cost often means more margins for a company, and management is often tempted to bet that the technology and provider will never go down (I saw this kind of behavior also for on-premises single datacenter deployments).

If you decide that having a plan to survive outages is not worth the money, don’t complain when something goes wrong. And no, you don’t need a multi-cloud strategy: you need a well-done multi-region deployment.

If half of the Internet is down because of a single provider outage, half of the Internet has to blame itself for this failure.

Old, but sadly gold meme image attached